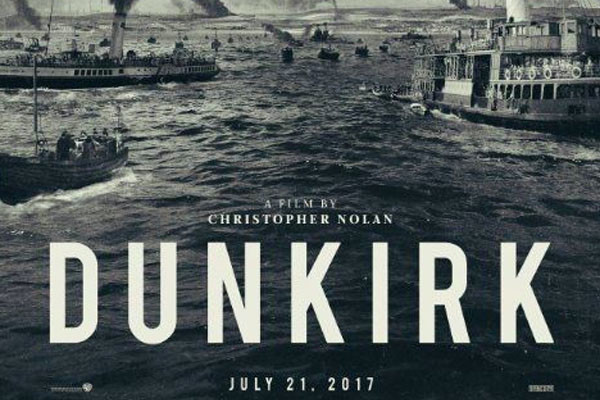

Dunkirk – Impresses and Entertains

July 24, 2017

On May 10th, 1940, the army of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany drove the Allied French and English armed forces to the very tip edge of occupied France. The Allies found themselves stranded on a strip of beach in the little French town of Dunkirk. This strip of land was so close to England that on a clear day, it was possible to see the fabled white, chalk cliffs of Dover. With the Allies trapped between the advancing Nazi forces, their backs to the sea, British prime minister Winston Churchill authorized a series of naval evacuations that was able to evacuate 338,226 men, among them, French, Polish, and Belgian, as well as English. While initially seen as a military failure, later historians have wondered if Dunkirk might have been the site of the battle that ultimately helped the Allies triumph in World War II.

Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk doesn’t provide answers for those questions. The director is more concerned with telling a series of interconnected personal stories. The first story concerns the struggles of Tommy (Fionn Whitehead), a British soldier who tries everything he can think of to get off the titular beach. The second plot thread concerns Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance), an ordinary citizen of Great Britain who decides to take his sizable yacht out on a rescue expedition to the Allied forces just across the channel. With Dawson are his son, Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney), and George (Barry Keoghan), a local neighbor who, he hopes, might “have” his “name in the paper”. The final plot thread concerns Spitfire pilots Farrier (Tom Hardy) and Collins (Jack Lowden), tasked with making sure the Luftwaffe cause no trouble for the evacuation in progress.

In the opening moments it seems as if these stories all take place at once. It isn’t until night falls on the beach with Tommy and Commander Bolton (Kenneth Brannagh), that the viewer realizes Nolan is once again up to his old tricks. Splicing and skewing the timeline is recurring motif in many of Nolan’s best known works, such as Following, Memento, and Inception. The director has lately come under criticism for the constant use this technique, and there is the danger that obsession with this form of storytelling could drag him into the realm of gimmicky self-parody.

In Dunkirk, Nolan’s technique sneaks up on the viewer. It isn’t until those first glimpses of night that the viewer realizes what’s going on. The potential drawback here is just how far of a loop this directorial choice will throw the audience. It immediately yanks the viewer out of the action, and those slow to catch up will find themselves having to contextualize all that’s come so far. This may require a bit of mental heavy lifting, and whether or not it proves a deal breakers will depend to a great extent on the tolerance level of the individual audience member. All I know is I didn’t mind it when it happened, and Nolan’s antics didn’t really interrupt the flow.

In hindsight, it’s easy to realize that the film’s three narrative threads take place over different times, and days of a whole week before the evacuation of Allied troops beings. Tommy story takes place over the course of a week, Mr. Dawson’s rescue expedition takes place over a 24 hour period on May 24th, the day of the evacuation. While Hardy’s plot thread takes up just a single hour of that same day. Nolan keeps his audience informed of these time skips by listing historical days and dates from the battle and rescue operation. There is nothing very novel or groundbreaking in these narrative flourishes. It’s basically a riff on a stylistic device best displayed way back in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. Again, the whole matter comes down to the individual tolerance level.

I came away both impressed and entertained by the film. The only note of caution, aside from Nolan’s editing, has to do with objectivity. I know I liked the film, at the same time, I find myself wanting to be sure that I can depend on that judgment. The film bears more than one viewing, and it speaks in its favor that I don’t mind going back for more.

In the end, the story Nolan has to tell seems based less on classic war movies like Saving Private Ryan, or The Longest Day. Instead, the narrative seems to harken back to the kind of survivalist fiction noteworthy as far back as Jack London’s To Build a Fire, where escape and the struggle for life are the main driving forces behind the action. What’s interesting is how Nolan seems to suggest that it was this very drive to live that helped cement one the greatest accomplishments of the twentieth century.