Alien: Covenant, Unimpressive

June 5, 2017

There is an old saying that “You can’t go home again”. There is also such a thing as the Law of Diminishing Returns. Alien: Covenant, the latest outing of the franchise, finds itself caught in an unworkable position between those two poles.

Taking place in the year 2041, a colony ship designated Covenant, is knocked out of order and orbit by a blast that presumably comes from a nearby collapsing star (the movie is vague on this point). The ship’s captain (James Franco) is killed in the ensuing accident, leaving his wife Daniels (Katherine Waterston), and the ship’s A.I. Walter (David Fassbinder) along with the rest of the survivors to fend for themselves.

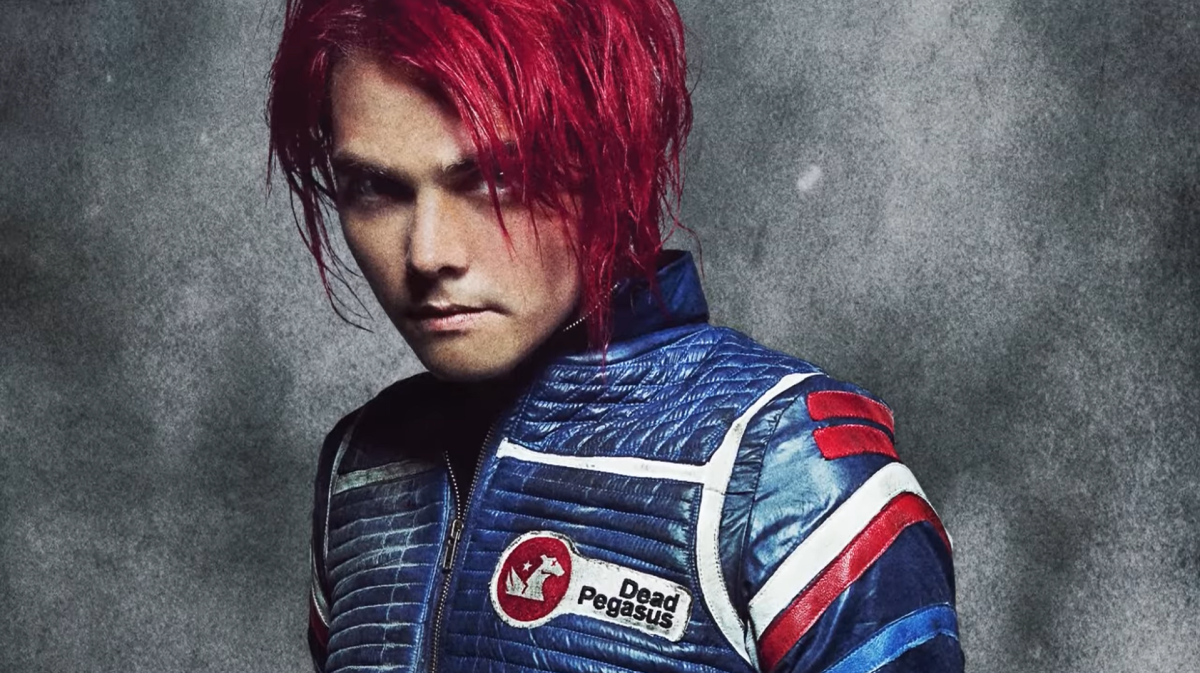

While making repairs, the Covenant picks up a distress signal from a nearby planet. After some debate, a rescue party is launched to the planet’s surface in search of survivors. Once there, the shore party stumbles across the wreckage of the spaceship Prometheus, along with its only survivor, and android named David (Fassbinder again).

There is something very suspicious about the whole set-up. David seems to know more than he tells, and possibly has a trick or two up his sleeve. Worse yet, one of the crew has picked up an alien germ from the planet, and it seems to be growing something inside his system.

I came away from this film feeling both unimpressed, and sort of letdown. After giving it some thought, I think I might know what’s wrong with the picture. If any of the above synopsis sounds like it could have been describing Ridley Scott’s original 1979 space chiller, that’s because in many ways all that Covenant can do is try and ape the story beats to the original first film.

It’s easy to do the math on this one. Katherine Waterston’s Daniels is not just meant to be a Ripley stand-in, or an homage. She is, for all intent and purpose, basically the exact same character as Sigourney Weaver’s. Waterston even went so far as to essentially admit that she was being asked to fill in as the de facto Weaver role for this outing in a March publicity interview. She decided to put that fact out her mind in the end. This is unfortunate because all the audience will get out of this film is a retread of what has gone before.

The film is marketed as a sequel to Ridley Scott’s earlier Prometheus of 2012. That film is still looked down on by most fans, and this factor plays into the finished product currently in theaters. Without spoiling too much, the audience does learn what happens to Rachel Noomi Pace, the main character from the last film. In some ways, it’s the most aggravating element of the film, because it signals that the movie is little more than an exercise in cash-grab course correction. What we see on the screen is Scott throwing his hands up in defeat and giving the audience a product that was already dead on arrival. The entire picture is the result feedback questionnaires.

It’s not too hard to see how we got here. Part of it is the obvious attempt by studios to either replicate the very first film’s success, or at least churn out a product that will keep the account books running somewhere near the black. The problem, however, is the same it’s always been. The fundamental difference between the original Alien, and all that came after is a problem lightning being captured in a bottle for one brief moment. What the first film gave audiences was a dark, and atmospheric mood piece, whose tone is forever at odds with the rest of the films in the franchise. The first film had the advantage of a script that had just enough novelty about it to make the final product seem both fresh, new, and exciting, while still wearing its influences without lapsing into unconscious plagiarism.

The difference between being influenced by earlier films, and flat out copying them are subtle. For instance, in his own review of the 79 film, Roger Ebert noted that Alien had a many similarities to John W. Campbell’s short story Who Goes There? The Campbell story went to inspire first Howard Hawkes, and then John Carpenter to try their hand at adapting the subject into The Thing. While all three films involve humans trying to defend themselves from an alien invader, Scott’s efforts differ from those of Hawkes and Carpenter based on the direction he takes his material, and how it ultimately branches off from theirs.

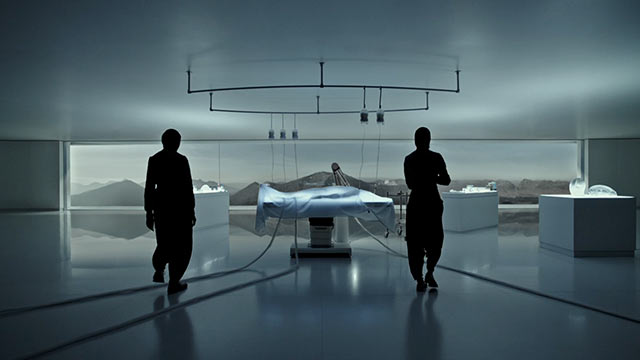

Both versions of The Thing revolve around the paranoia of the Cold War, and the question of identity. Scott’s work is more straightforward, revolving around the idea of a kind of Lovecraftian first contact, plus a riff on the Hunter/Hunted trope. What sets Scott’s efforts apart is the underlying sense of cosmic dread. The first time audiences saw the skeletal remains of the alien pilot in the ship designed by H.R. Giger is important for the very alien sense it brings to the proceedings. The characters realize on a gut level that they have entered another world in a very literal sense. What makes it so disturbing is suggestion it gives that we have moved to the very threshold of human comprehension and normalcy.

Giger’s design for the zenorph ship hints at a mode and form of life that is outside every expectation we have about the universe. It implies that the kind of life that could both build such a ship, and house such a life-form is not only hostile, but also outside the very bounds of sanity. We’re left wanting to try and understand what kind of life we are seeing, all the while, in the back of our minds, the uncomfortable idea gnaws at us that to fully understand what we’re seeing could very well drive us mad.

It was this sense of cosmic fear and threat that Scott was able to tap into his first time out of the gate. The problem with such stories is that it’s pretty easy for the human mind to adjust to such tropes. This is helped by the realization that what looks inhuman originally came from a human mind to begin with. Therefore, nothing we see on the screen is ever truly alien. This is a knowledge that must be somewhere in the back of our collective minds, because all the others films are able to give us mostly wall to wall action combined with jump scares and mediocre gross outs.

In some ways, Alien: Covenant highlights the problem with film like Prometheus, as well as itself. Part of the reason I didn’t mind the earlier film was because I thought it meant Scott was going in a totally different direction. We may never know if it would have worked, because audiences by now have come with a certain set of expectations for any xenomorph flick. Go against those expectations, and you risk losing your audience. It makes me wonder if maybe Scott wouldn’t have been better off making both Prometheus and Covenant as entirely different films unconnected in any way with the Alien franchise. At least that way would have left the audience guessing and open to new experiences.