‘I Am Not Your Negro’

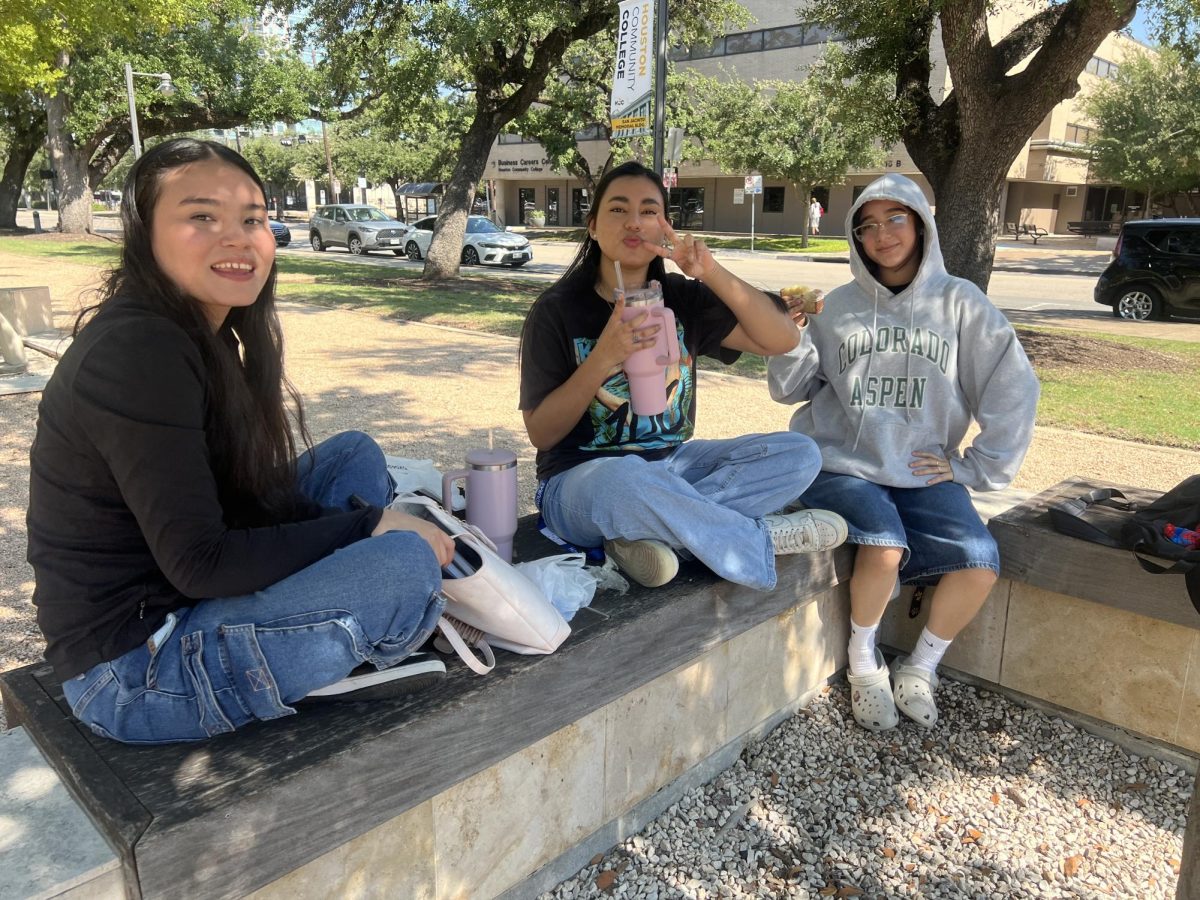

Anti-integration rally in Little Rock in I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

March 7, 2017

Being raised in Oakland, California — home of the Black Panthers — one might be safe to assume that I’ve always been black and proud. Truthfully though, becoming comfortable within my own skin and the use of my own voice has been a learned process.

I was not allowed to watch movies like “The Lion King” as a child. My mother was concerned that an animated movie was set in Africa for the first time in my young life only featured animals as characters. I was always aware that film and media have a way of pushing an idea, whether good or bad, onto the viewing public.

As I grew older (and enrolled in an amazing interpersonal communications course), I realized that the way viewers interpreted what they were seeing was based on their own frame of reference. Just as my mother had been opposed to the viewing of a cartoon film essentially depicting Africans as animals, there were others who felt that the film would increase awareness of the beauty of Africa and an understanding of the circle of life that is critical to the survival of our planet.

“I Am Not Your Negro” will not have the same double context.

“To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time,” said novelist and social critic James Baldwin.

Police brutality has always been an issue within the black community. Growing up, there was an agreement throughout my own community that If you see the police stop anyone, you yourself were to stop and ask if that person was safe and if there was anyone they would like you to call to make them aware of the situation. The reality was that although I was a child of the 1990s, these practices which had been put in place during the 60s were still necessary and this fact most certainly impacted my outlook and perspective of the treatment of blacks in America.

Directed by Raoul Peck, “I Am Not Your Negro” is based on a 30-page manuscript written by Baldwin and depicted through a series of historical videos, movies, commercials and public speeches.

The film, based on the never-finished book “Remember This House”, is partially a memoir of the author’s recollections of African-American leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. — all killed before the age of 40. The film to me stands more as a premonition to the future of the plight of blacks in America.

Baldwin’s words, though meant to be descriptive of the American climate in the 60s and 70s, speak poignantly to the struggles of today. There are no “talking heads” as movie buffs refer to on-camera interviews, which further drives home the point that America’s past is our present. Had it not been for the black and white vs. color images chosen by Peck, one would not know that the footage of protesters being held at bay by police dogs and officers clad in riot gear ranged from the 60s to Ferguson protests of 2014.

In our current time, we have experienced victories such as the election of our first African American President Barack H. Obama. Yet, the November 2016 murder of a close friend and well known musician Will Simms by white supremacist in the California Bay Area (not featured in the documentary) can be easily mistaken for a story from the Civil Rights era. The only difference between the offenses (which we now know to be false) of Emmett Till and Will Sims is that Till was believed to have committed the sin in the Jim Crow south of speaking to a white woman while Sims’ was simply being a black man in the aftermath of a racist, sexist and xenophobic presidential election.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” Baldwin said.

As much as we may like to think that America has changed and that the issues we have been fighting against have been addressed the reality is, had this been true, would we really have a need for movements like Black Lives Matter? Would we even have to discuss the deaths of Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Philando Castile and Oscar Grant?

“People finally say to you, in an attempt to dismiss the social reality: ‘But you’re so bitter.’ Well, I may or may not be bitter. But if I were, I would have good reasons for it, chief among them that American blindness or cowardice which allows us to pretend that life presents no reasons for being bitter,” Baldwin said.

When we look at the great strides that have been made in regards to the black struggle, the laws passed nearly half a century ago that assisted blacks such as the Fair Housing Act of 1968 may stand as proof to many white Americans that unfair treatment of blacks have improved. It may even lead them to wonder why blacks still seem so “bitter”? Blacks however are reminded of unfair housing practices of a not too distant past as they grapple currently with gentrification causing many blacks to be once again uprooted from the only homes they have ever known.

‘I Am Not Your Negro’ speaks to these truths without having to literally speak them. The film tackles the social injustices of the past and present with many images we are familiar with woven together to reassert the film’s title.

Although as a collective the history of the black experience in America may fall under the general category of horrendous, ‘I Am Not your negro’ shows the diversity of reactions to that experience providing historical context to not just the movements that helped to push blacks in America forward but provide context to the men that led those movements. Martin’s non-violent fight for civil rights, Malcolm’s by any means necessary approach and Medgar’s demands for the advancement of black people were all made even more clear through a montage of news reels and other rare footage.

Viewers will definitely walk away with clearer perspective of what life was like for blacks in the 1960s fighting for Civil Rights as well as today, still facing police brutality and the weight of racial oppression. What then happens if no one views it at all? If a political and socially conscious Baldwin film plays in a theater, but there is no one there to view it, does the consciousness transcend?

I urge anyone reading this to, if you have not already, go and view this film. Encourage others to as well. Not because it received an Academy Award nomination along with countless other honors. Not because Samuel L. Jackson narrated it, but because there is clearly a disconnect between black and white America especially in terms of the struggles we both face which the documentary makes painfully clear.

The dialogue of race is a sensitive one but one that desperately needs to be addressed. Barriers faced by blacks as depicted in the film are not figurative, these barriers are literal and history has shown them to have been intentional.

“What white people have to do, is try and figure out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man, but if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it,” Baldwin said.