Maintaining and preserving sacred grounds

On a Saturday morning you will find most people lying in bed, waking up late, or in my case taking a morning class here at Houston Community College. However, on the second Saturday of every month, from 8am–noon you will find Professor Angela Holder and her students volunteering at the historic College Memorial Park Cemetery.

Holder began sharing this volunteering opportunity with her students in spring 2011.

Three soldiers died on Aug. 23, 1917, as a result of the Camp Logan Mutiny Houston riot of 1917. Two died that night and were buried at College Memorial Park Cemetery. The third soldier died a few days later due to injuries and is buried at the Holy Cross Cemetery.

Holder says that the two soldiers were, “hurriedly buried from what I could see because they never had headstones.”

Working with the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum and the Veterans Administration, they were able to finally give the soldiers a headstone after about 100 years.

The riot occurred shortly after the United States declared war on Germany in World War I.

Holder explained that the riot was the soldier’s response to the issue of police brutality committed against one of the military officers in the Third Battalion of the black Twenty-Fourth United States infantry.

The black contingent encountered racial discrimination from the moment they stepped foot in Houston. While many of the men had been raised in the south and were familiar with segregation, as servicemen they expected equal treatment. However, police and other public official considered the arrival of black soldiers as a threat to racial harmony. Some police officers frequently harassed both civilian and soldier African Americans. Professor Holder noted that there were numerous other incidents between the citizens, police, and the soldiers regarding the enforcement of the Jim Crow segregation in Houston.

Around noon on Aug. 23, 1917, a black soldier was arrested by policemen for interfering with their arrest of a black woman in the Fourth Ward.

Early in the afternoon Corporal Charles Baltimore, one of the twelve black military policemen with the battalion, inquired about the soldier’s arrest. After an exchange, the policeman hit Baltimore over the head and he fled. The police fired at Baltimore three times, chased him into an unoccupied house, and took him to police headquarters.

Baltimore was soon released, but a rumor had been started that he had been killed by police even though he came back to the camp later that afternoon.

The men were still upset that there was a possibility that he could have been killed.

In the riot 15 whites including four policemen were killed, 12 others were seriously injured including one policeman who later died due to his injuries. Four black soldiers were killed, including two who were accidently shot by their own men. A National Guard Captain was also mistaken for a policeman and killed. Sergeant Vida Henry of the Company who led the soldiers in the riot shot himself that night.

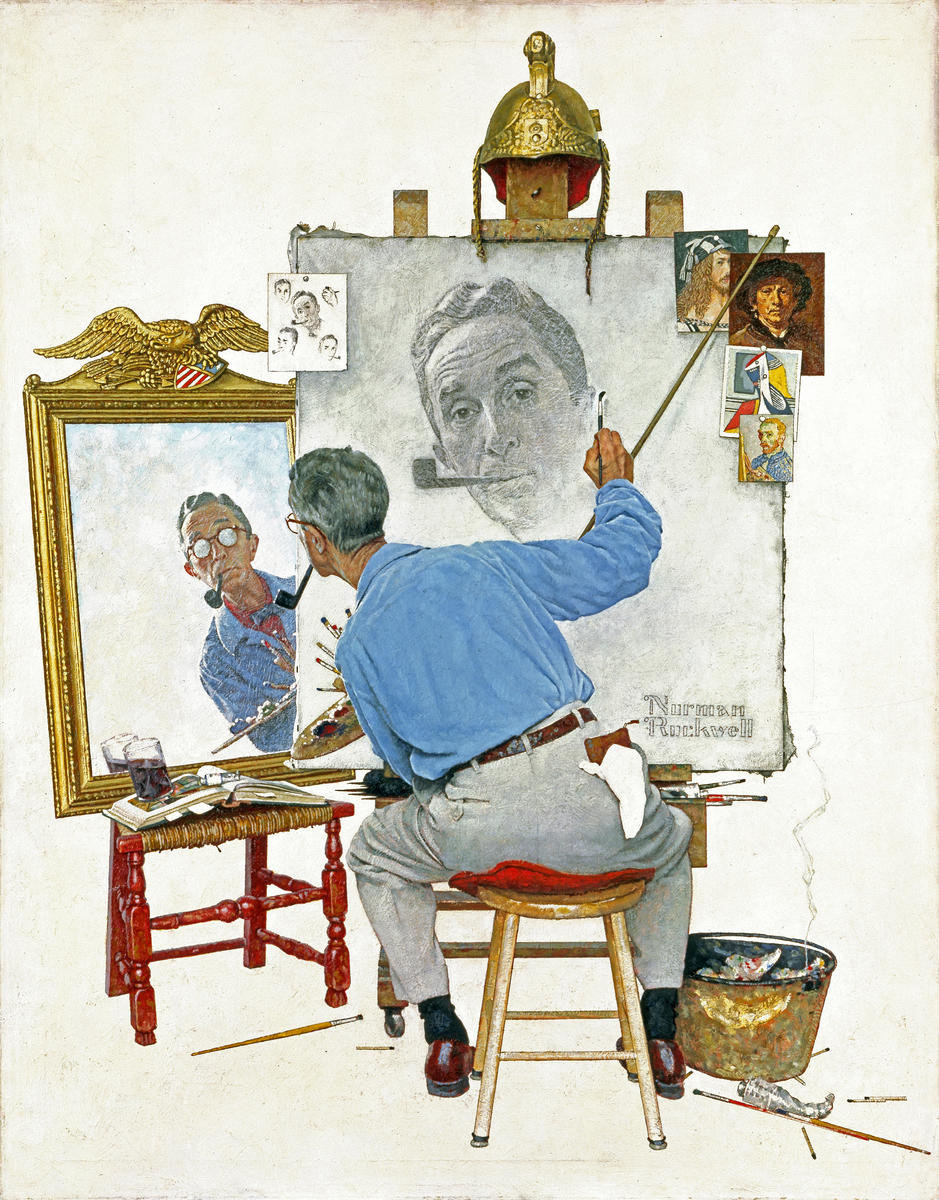

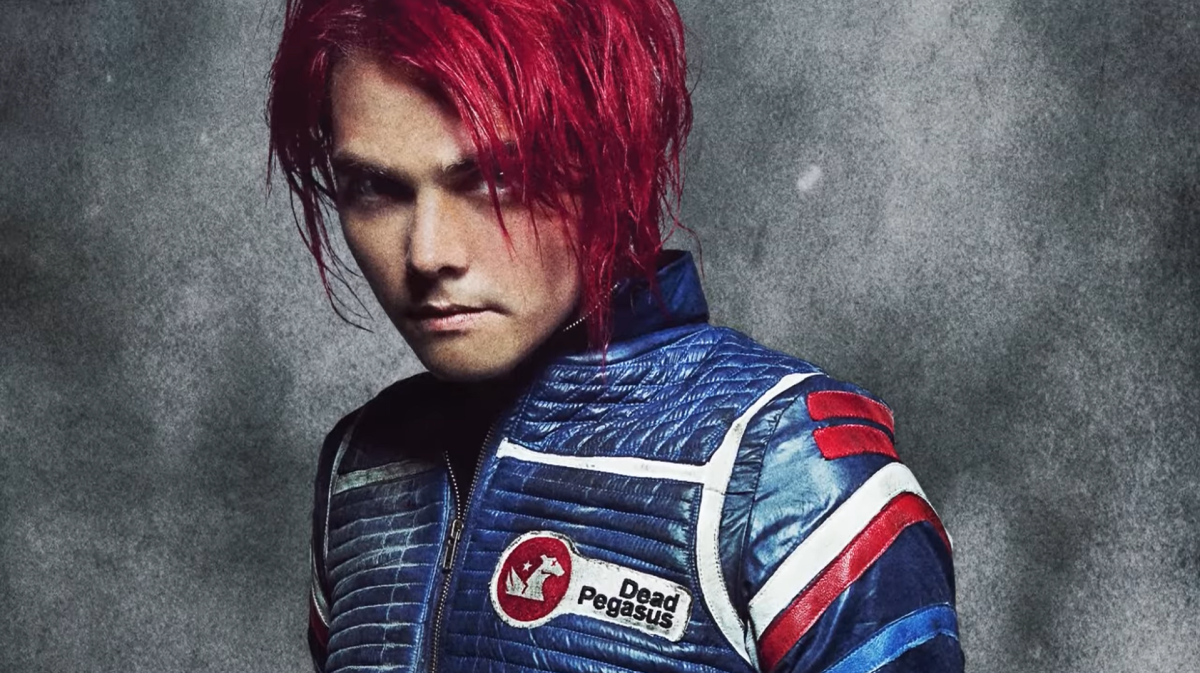

HCC Professor Angela Holder in her office.

“Everything pretty much came to a head on that day, August 23,” noted Professor Holder.

Randy Riepe serves on the Board for College Memorial Park Cemetery Association and is also a past president of the board.

Professor Holder remembers meeting Riepe when she visited the cemetery to try to find the grave of the soldiers. “He was there by himself sitting there with his lawnmower and the cemetery was overgrown and needed cutting. He was so nice and helpful. I was so grateful for his help I said my students might be interested in coming out to help.”

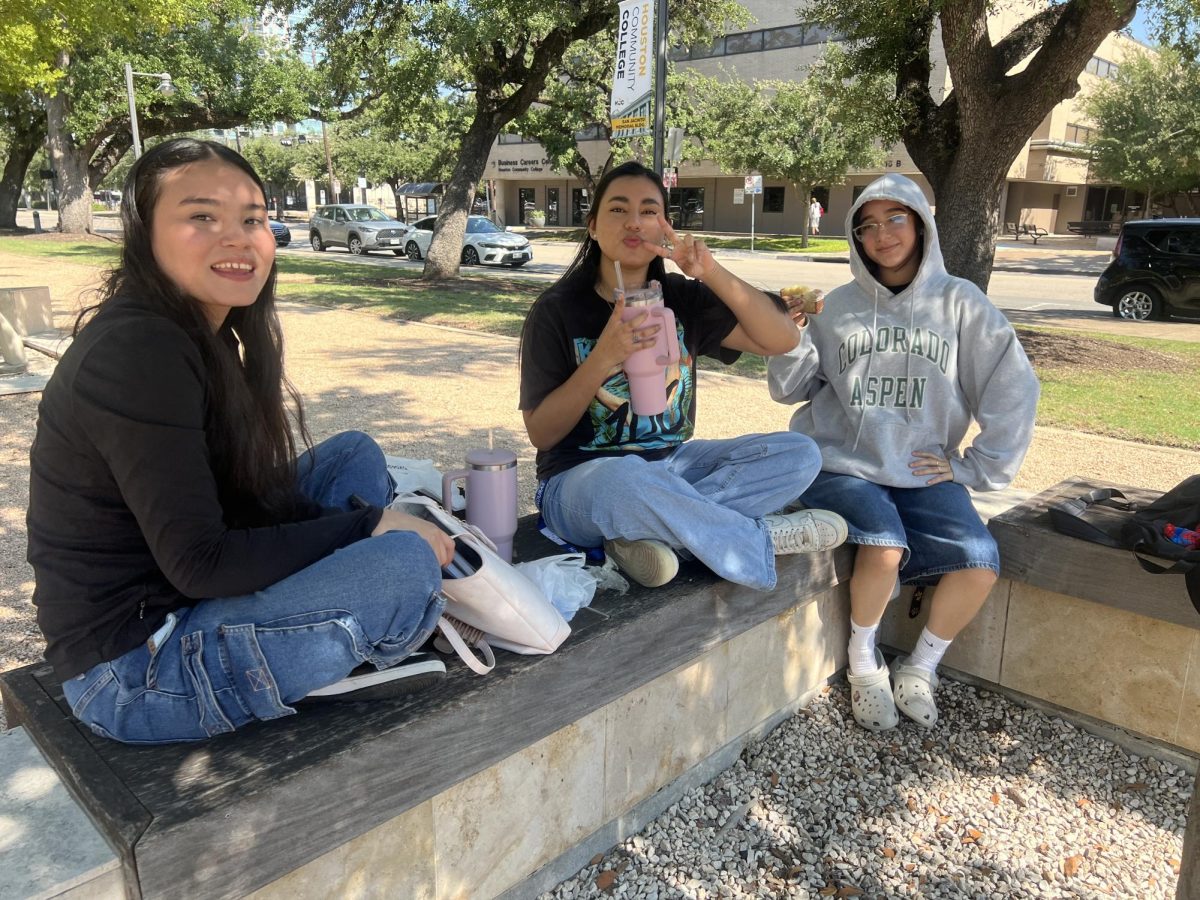

HCC student Raju Sapkota explained how student work in groups, “Every group was assigned work like picking up trash, cutting old and dead trees, picking up sticks and throwing all those into a dumpster.” Sapkota said that she knows their work is appreciated by the cemetery custodians.

It’s hard work maintaining a cemetery. HCC student Hang Yang said, “It was not easy work and everyone worked really hard….after 11 am the sun got bright and really hot…”

Students cut grass, remove trees that have died from drought or old age, they fill sunken spots where graves are and more.

“At first I was expecting we were going to be planting flowers, doing light stuff but we were using chainsaws and lawnmowers, there was a few snakes here and there,” said HCC freshman Kyana Hatfiel-Mills, “I had never used a lawnmower or cut grass before, I thought it would be fun but it was hard. It was brutal.”

Mills added that she enjoyed meeting other history students and learning about the cemetery’s history.

While her students earn volunteer hours, professor Holder gives them bonus points. “To see the cemetery as good as it is now to when it was overgrown before is really nice. Pretty much what we are doing now with the students is maintaining,” says Holder.

Through the volunteer work, students learn about Houston’s history.

“When they see some of the tombstones and they see the years, that the former slaves, and former professionals that made Houston what it is and they can see some history there,” says Holder, “It’s really like a classroom experience as well.”

Holder believes that it’s “my generation’s duty to teach the future generation to give back. I’m pretty much doing what was done for me and my generation. So I’m just passing it on. Hopefully when you guys get out in the professional world, that you guys will give back too. You gotta pay it forward.”