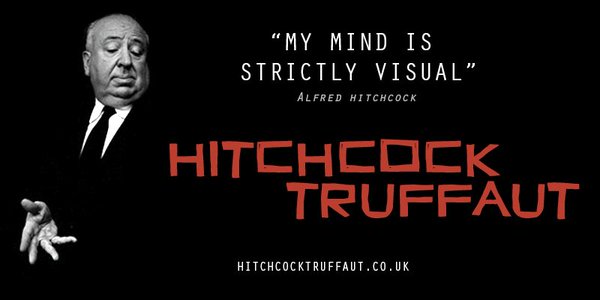

Alfred Hitchcock, A Continuing Wonder in Film

October 29, 2016

It is one of the most iconic moments in cinema history. A woman (played by Janet Leigh) on the run from the law finds a temporary safe haven in an off-ramp rest stop known as the Bates Motel. While taking a shower, this woman becomes the victim of an anonymous serial killer who draws back the curtain to knife her, over and over again, until at last the woman lies dead.

The infamous Shower Scene in Psycho is one those moments in film that manages to dig a space for itself in the minds of a lucky few viewers. That film was directed by British filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock, and its impact on audiences in 1960 was almost immediate. The film’s release was one of the first instances where record crowds would line an entire block in their eagerness over a new release. The fact that the film succeeded on word of mouth alone is a testament to its quality. Hitchcock made the controversial decision to let the film promote itself, refusing to let the cast do the usual rounds of promotional interviews and TV appearances that are still part of the Hollywood marketing machine. Psycho proved it was able to hold its own, and one member of the audience was more than thrilled by what he saw. He was inspired.

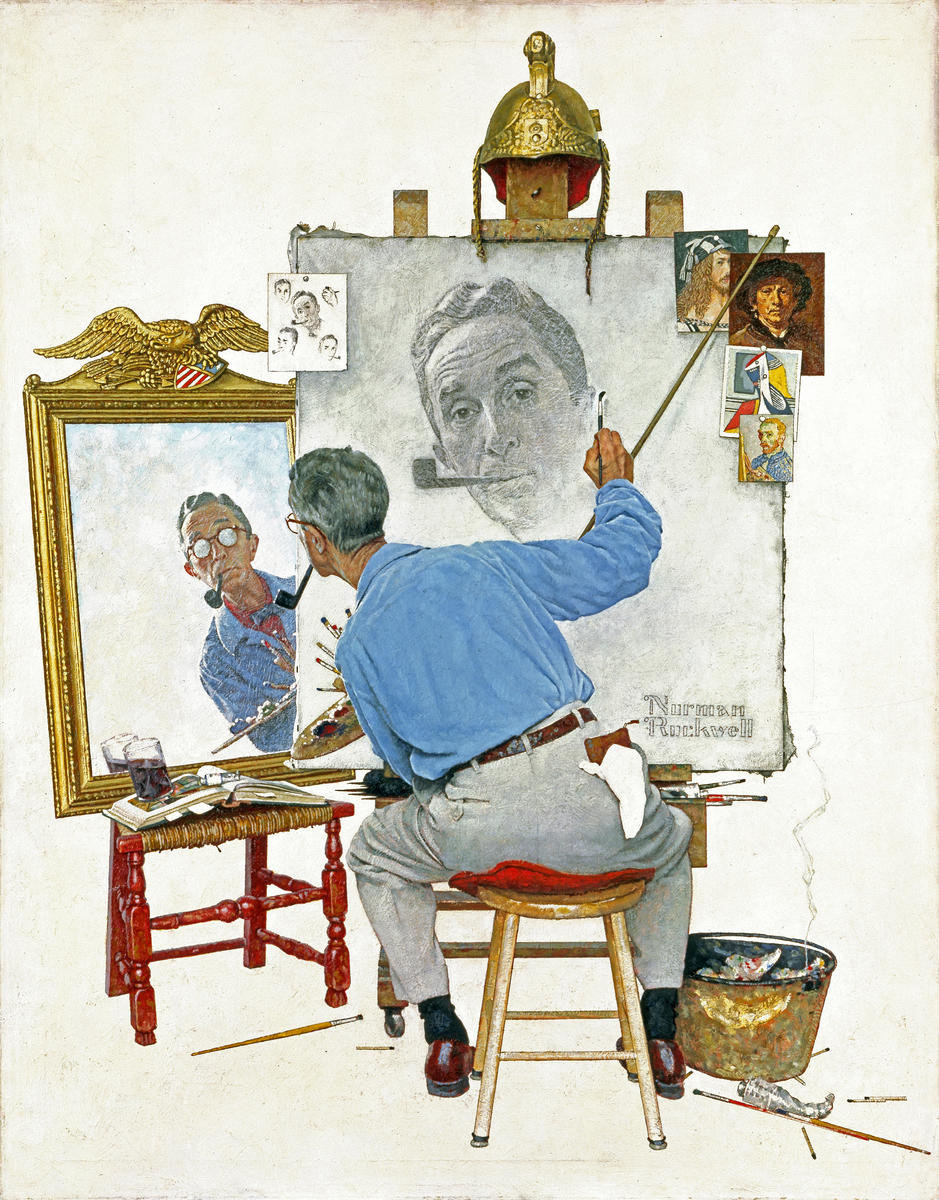

In 1962, French New Wave director Francois Truffaut wrote to Hitchcock, suggesting a series of book-length interviews to be held over a number of days. He would be given the time and space needed to both explain and defend his career and make a case for the “Art” of movie-making in general. Hitchcock agreed, and the book was published in 1966 under the title Hitchcock/Truffaut. Much like Psycho, Truffaut’s interviews left an impact on the industry, however this one was more subtle and unnoticed, except by a few. The handful of directors that made up the Movie Brats generation of filmmaking, such as Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, were able to rally around the book as a kind of Cri de Coeur.

The interviews of Hitchcock/Truffaut are the subject of Kent Jones’ new documentary of the same name. That idea of a rallying cry, and how it has changed over the decades is crucial to an understanding of the material Jones is working with. Over the length of its 80-minute running time, directors like Scorsese, Peter Bogdonavich, and Wes Anderson sing the praises of both filmmaker’s and their interviews as a kind of gold standard to which artists in film should aspire.

It must be kept in mind that both Truffaut, Scorsese, and Spielberg were the first to make these claims way back in the Vietnam Era. Here, the same claims are made, and yet the passage of time has created a literal world of difference. During the establishment of Cahiers du Cinema the argument was all about the validity of film as an artistic medium. In today’s post-Pixar age, those claims have shifted. Before the claim of film as Art was considered reactionary. Now the claims carry a more curative, preservationist slant. The spokesmen of the Cahiers age seem less concerned now with film as Art than with the type of stories film can tell.

At the heart of Jones documentary lies an implicit plea that modern audiences not forget where their favorite movies have come from. Nor should they forget the different kinds of stories film can tell. In an Age of Blockbusters where the comic book dictates the main public tastes, Hitchcock/Truffaut suggests that there always alternative choices for the kind of stories that can be told. Early on in the film, Truffaut observes that Hitchcock’s particular “type of cinema irritates the critics because of your casual approach to plausibility”. To which Hitchcock sums up with the reply, “Logic is dull”. What’s curious is that he doesn’t seem to be discussing the implausibility of a film like The Avengers, but something much more complex. Later on Truffaut asks “Are dreams important to your work?” Hitchcock’s response is telling, “I’m never satisfied with the ordinary. I can’t do well with the ordinary.” It is dream logic, not a simple blockbuster mentality that drives his work. It is an aesthetic that does not fit any of the current film categories. It suggests that the real key to the kind enchantment that stories provide is not in hitting the audience over the head with explosions, but in tapping into the kind of poetry that can best be discovered in dreams.

For this reason, Hitchcock’s oeuvre is an unintentional anomaly. He didn’t set out to be an outsider artist. By standard of his day, he was a popular entertainer along the likes of Spielberg. Today, however, with the shifting tastes of audiences over time, we have turned a mainstream artist into a kind of freak. Something that is hard to grasp or understand. It can be interesting to see how these differing standards play off one another. However, in the end, most movie goers are doing themselves a disservice by depriving themselves of the kind of alternative cinema offered by a genuine classic artist. The imagination is multifaceted, and those who care about it, and the telling of stories, owe it to themselves to check out the work of one of Hollywood’s great pioneers. All that is needed is something that can serve as a proper, first introduction. From that perspective, Hitchcock/Truffaut is probably one of the best introductions out there.