Rodeo Hall of Famers honored

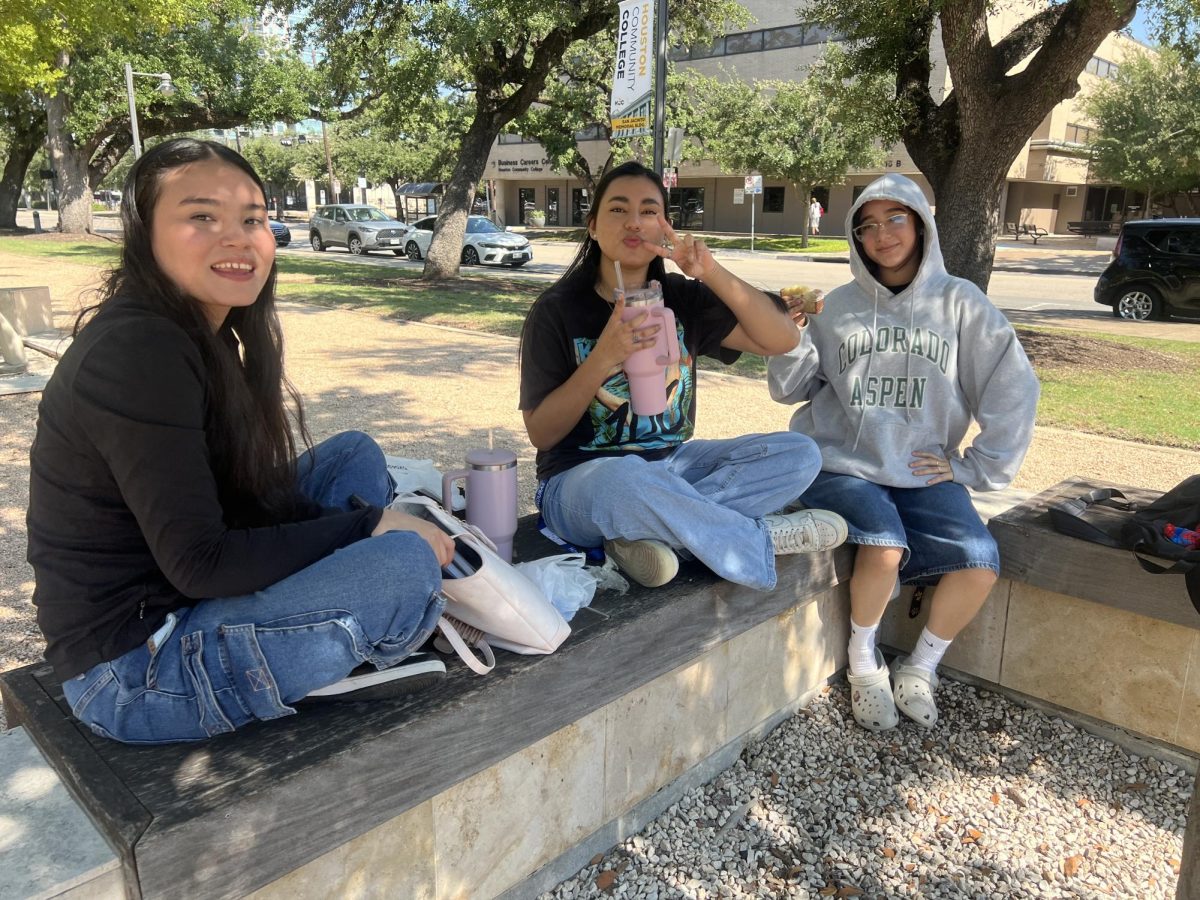

African-American cowboys pose during Black Heritage Day at the Houston Rodeo along with Rodeo President Joel Cowley.

March 13, 2016

With the help of two Houston based museums during Black Heritage Day, Several African-American rodeo legends were recognized at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

The American Cowboy Museum and the Buffalo Soldier Museum were both invited by the Rodeo Black Heritage Committee help celebrate two African-American cowboy hall of famers and provide insight into their careers for future generations.

The honorees include: Myrtis Dightman, Lloyd Randle, Nathan “Mama Sugar” Jean Sanders, Harold Cash, Lloyd Randle, and Mollie Stevenson. They helped multiple guests and rodeo attendees to learn about the rodeo’s multicultural branch.

President and CEO of the Houston Rodeo Joel Cowley says, “The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo serves the Houston community, and we want to serve the entire Houston community by bringing people out and inviting them to enjoy what we do out here.”

Black heritage day and Go-Tejano day are two of the Houston Rodeo’s ‘special days’, which celebrate the contributions of cultural groups to western culture.

Cowley continued, “Black Heritage day and Go-Tejano day are designed to do that, to reach out to different areas of the community bring them in, and let them see what we do.”

The African-American Hall of Fame riders ultimately had to earn their place at the top. All of them lived through the Civil Rights struggles in mid-20th century Southern U.S.

Myrtis Dightman, also known as the Jackie Robinson in professional bull riding, was a seven-time bull riding finalist and the first ever African-American to compete in a National Finals Rodeo. Starting off as a rodeo clown protecting riders from the bull, Myrtis found himself riding the bulls by 1964.

When asked about the racism spread through the old South, Dightman says, “That didn’t bother me too much. I went to a couple rodeos that I couldn’t go at the same time because I was working…but rodeo has been good to me, I have been all over the world two or three times, I’ve never been in a fight, never been in an argument and never been in jail.”

Dightman told himself that he would win the world one day. Promoting—that it’s the way you carry yourself. Unfortunately, he only ever achieved the runner up spot. Later on in his career, Dightman saw to the training of Charlie Sampson, the first ever African-American to ever win the National Finals Rodeo.

“I did not have any help, I paved my own way and everything,” Dightman says. Now living in Crockett, TX, the retired rodeo-man expressed how he would like for the new generation of young, particularly African-Americans to be more involved in rodeo life. Aware that the numbers of black riders are decreasing, he still hopes for individuals to carry on the tradition and continue to open new doors within the western sports.

Dightman is the founder and Trail Boss of the Prairie View Trail Riders—the first official black trail riding association—where he looks to give insight to young individuals about the rodeo lifestyle.

A colleague of Dightman and fellow hall of fame inductee, Harold Cash, faced similar issues as a professional African-American bull rider. Growing up in Kendallton, TX, Cash watched his town’s local rodeos on Sunday, one of only five rodeo opportunities available to blacks at the time. After being introduced to the sport, his mentor Willie Thomas took him on the road, where he traveled around the U.S. to places like New York, Chicago, D.C. and New Jersey.

Cash said, “Without the sport of rodeo, then I probably wouldn’t have obtained a bachelors in science degree from Prairie View A&M.”

Later he became the sole owner of the Tie Down Saloon in 1985 and formed the All-American Rodeo Association with Dightman. Cash emphasizes the doors that the rodeo has opened for him.

The Harold Cash Living Legend Rodeo puts on a rodeo every first Saturday in June in Raywood, TX to honor deceased African American cowboys.

Also, a member of the National Multicultural Hall of fame Cash says, “I have seen the back-end of segregation. People like Willie Thomas and Myrtis Dightman, they really broke the ice for black cowboys.”

Continuing he says, “It was just a way of life back then, it wasn’t the cowboys. For the cowboys it was man against beast…The places you went to made it segregated.”

Practical tools made the experience at the rodeo tougher for African-Americans. The bull rider explained how at times, the timer of the ride would double the 8-seconds of regulation time for the black rider.

Cash further expressed his appreciation for rodeo figures like Dightman and Thomas, whom he watched as a young man and later started to work alongside. Recognition in places such as the Multicultural Hall of Fame and the American Cowboy Museum gives individuals the chance to act as a role model for future generations.

“When I accept any one of these awards, I tell them when you’re looking at me, you’re looking at a 1000 cowboys, it’s not about me,” stated Cash, adding, “The doors have opened for blacks, but the wheels are still turning slow.” He is encouraging young individuals to do what they love and work their hardest in order to achieve their dreams.

Subsequent to Harold Cash’s expression, 15-year old bell-racer Zoria Crawford looked on at the numerous displays of her predecessor’s achievements and awards.

The Hightower High School freshman spends her free time as an active member of the Fort Bend 4-H and the Junior Livestock Committee of Fort Bend, both of which she holds leadership roles in.

Zoria also takes part in a Youth Rodeo Camp in the summer, teaching kids bell racing and pole bending. Her audience ranges from 7-year-olds to 9-year-olds, permitting her to provide hands-on demonstrations and creative teaching methods for children.

Referring to seeing the accomplishments of the inductees, Zoria says, “That’s a happy feeling.”

Traveling around Texas to compete in Angleton, Egypt, Montgomery and Pasadena, she has been crowned pole-bending champ for three years straight and All-American Cowgirl by the All-American Youth Rodeo Association.

Placing first in numerous competitions, Crawford says she believes she can get to the heights of professional bull riding pioneer Dightman, despite being female and African-American in a predominantly male sport.

When speaking about riding she says, “I want to do it until I can’t do it anymore,” proving that her optimistic attitude and positive actions keep her going, along with those around her.

Crawford says she influences her friend by motivating them to do what she does, but whether or not she is riding or assisting her community Crawford made it known that she would not be where she is today without her father Willie Crawford Jr.— whom she “thanks god for.”

Similar to Crawford, Mollie Stevenson, a hall of fame cowgirl and the owner of the American Cowboy Museum, says opportunities where all four of her colleagues can come together are rare. The idea for the exhibition was created by the American Cowboy Museum, but brought to fruition by the Black Heritage Committee with a purpose to give exposure to the inductees.

Crawford epitomizes what professionals—like Harold Cash, Lloyd Randle and Charlie Sampson—say about how the tradition needs to be kept alive. Not an individual who uses their talent as an opportunity to become famous, but as a person who continues to inspire and open doors for others, whoever they are. Her dream, she says—both concise and attainable—“To become pro.”