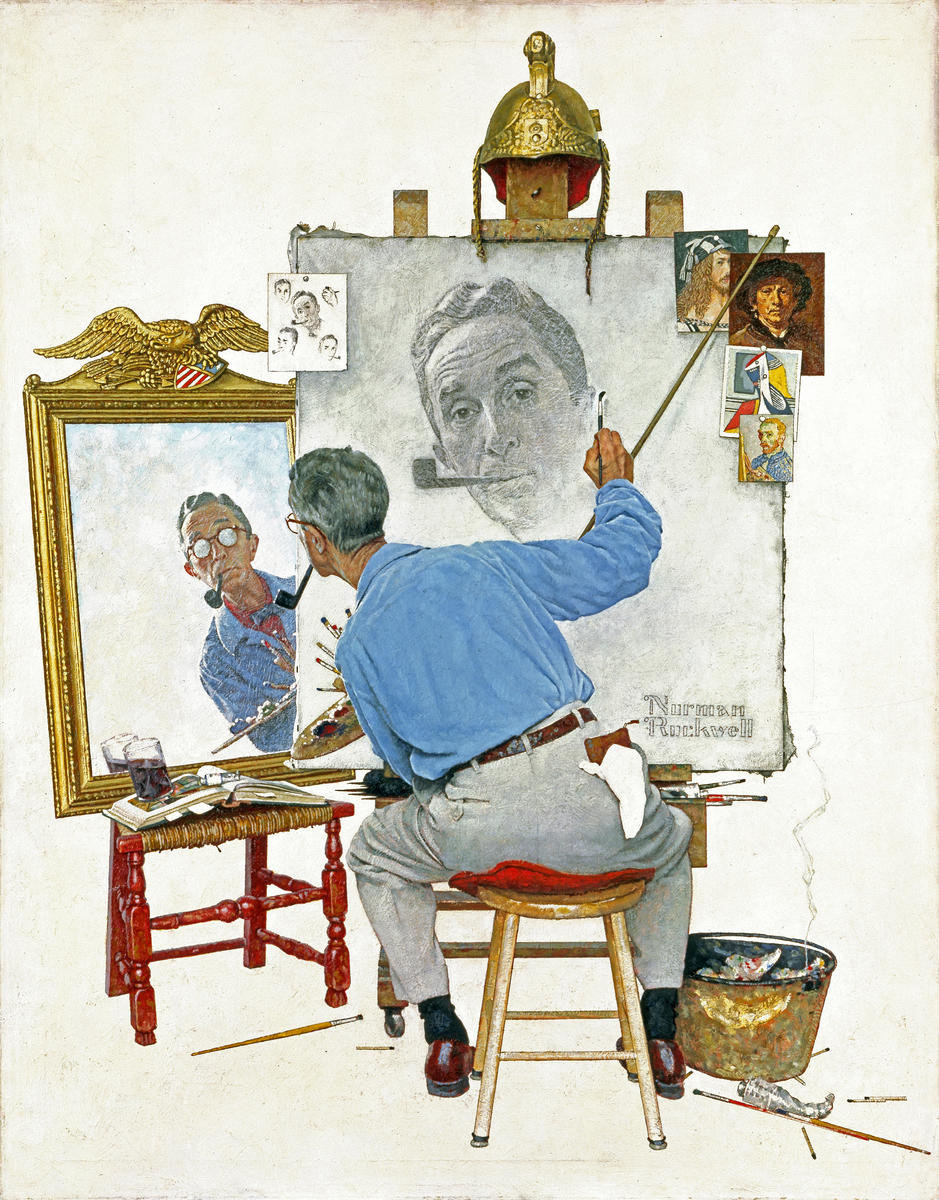

Who is Norman Rockwell? “It’s that illustrator whose work is hanging from my grandmother’s living room,” answered one. “It’s that guy from Lana Del Rey’s great album,” answered another one. The truth is, Norman Rockwell has been one of those artists who lost against time, whose talent and creativity to capture American life have been reduced to only nostalgia by later generations.

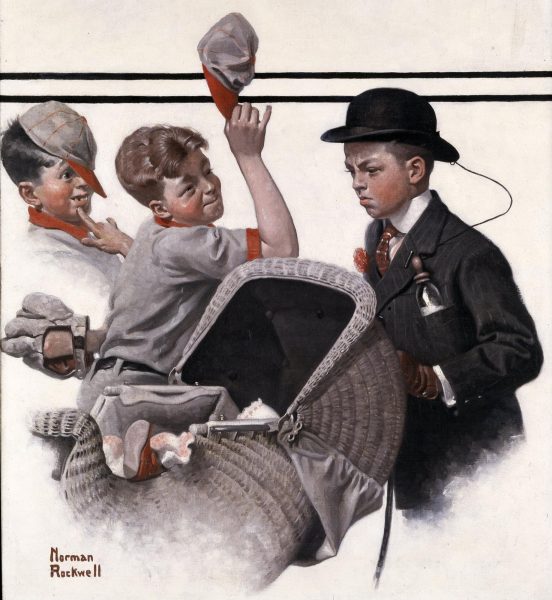

It’s easy to criticize his work now, after all, the concept of Americana and the society he lived in is not the same as ours, and his illustrations often focused on a very narrow slice of 1940s and 50s life, excluding minorities.

You might be wondering: “Why should I read about him? It’s going to be another boring article about a guy whose existence I acknowledge but I do not recognize him.” And to be honest, that’s completely fair. However, if you bear with me, I’ll try to explain why his work and his social and political perspectives are still relevant, even in our 2025, Gen Z, ‘labubu-obsessed’, Taylor Swift, Tik Tok culture, society.

Rockwell was more than the guy behind sentimental holiday scenes, he was a storyteller of American hopes and contradictions, one whose work reflected the nation’s ideals and its blind spots. Rockwell’s work brought hope, represented realities, and communicated stories in ways few artists have. In learning about him we might find that same hope and representation he gave to the American people in turbulent and chaotic times.

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City on February 3, 1894. The story goes that he always wanted to be an artist from the beginning, he attended art school in Manhattan and was commissioned to paint Christmas cards at the age of fifteen. At twenty-two he illustrated his first covers for the magazine Saturday Evening Post, which (fun fact), was founded by Benjamin Franklin’s associates in 1821.

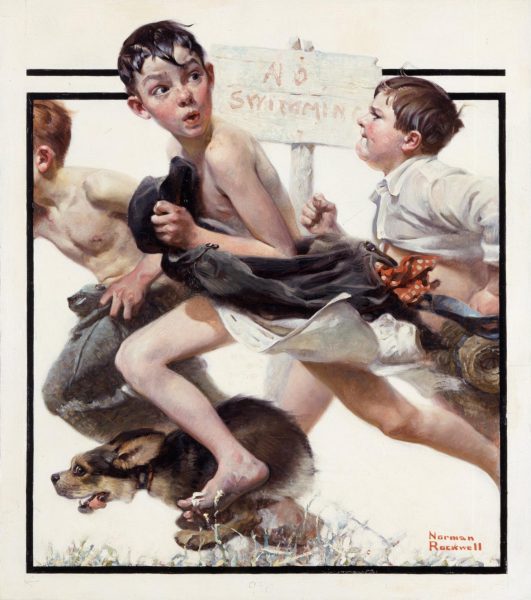

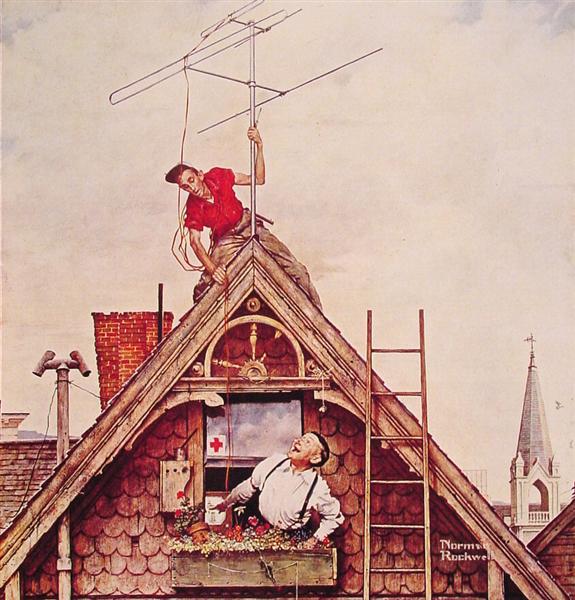

Rockwell went on to create dozens of iconic covers for the Saturday Evening Post and Boys’ Life magazine, where he served as art director. He also illustrated advertisements, movie posters, holiday cards. Pretty much everything that you’d see in your city or town. He was everywhere.

While working for these magazines, Rockwell started to shape and be part of famous concepts that may feel foreign to us today: Americana and the “American Dream.” His talent to see and understand frames of real-life moments allowed him to illustrate those specific moments and instantly, any person could know his art by his style and the concepts he was trying to communicate. Family life and traditions, a love for nature and animals, baseball, cars, highways, television, suburbs and post-war modern American life all became hallmarks of his art. He once said: “Right from the beginning, I always strived to capture everything I saw as completely as possible.”

By this time, Rockwell had gained fame. Every person who saw him would say: “Thanks for illustrating what my neighbor does!” It is important to note that he didn’t consider himself an “artist”, struggling to see himself as anything beyond an illustrator and storyteller. In my opinion, he was too humble to recognize his ability for art and the artistry of his work.

Despite his success, Rockwell faced criticism for underrepresenting minorities. If we analyze the covers I shared in this article, most of those covers depicted white, middle-class Americans enjoying suburban life. But was that reality for all Americans? What about the South in the 1930s and 40s, immigrants, or the impact of the Great Depression? These topics were largely absent from his early work, in part because the Saturday Evening Post’s conservative audience and editorial guidelines discouraged political content.

On January 6, 1941, Rockwell attentively listened to the words of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt about the four freedoms in the world: “The first is freedom of speech and expression. The second is the freedom of every person to worship God in his own way. The third is freedom from want. The fourth is freedom from fear.” Inspired by those words, Rockwell created his breakthrough artwork: The Four Freedoms series.

These covers were his first major incursion into political and social issues. Remember that the country was still trying to get out of the Great Depression and it was about to enter the Second World War. During these turbulent times, Rockwell’s illustrations brought hope to millions. The Four Freedoms covers didn’t just illustrate Roosevelt’s speech, they reminded Americans of the values worth defending, offering inspiration in a time of global uncertainty. While he didn’t fight the war, his bravery was represented by his powerful messages of hope through his art.

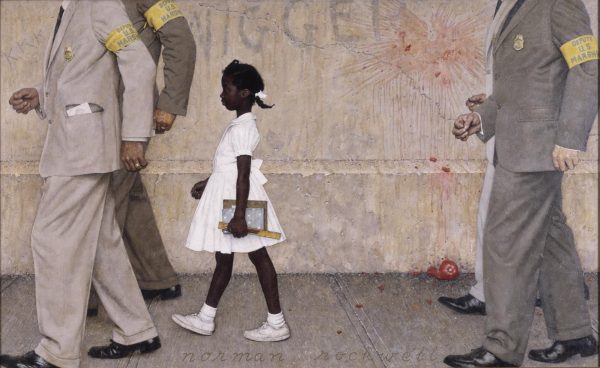

Rockwell would not fully engage with political and social realities until after leaving the Saturday Evening Post. The explanations of why he resigned from the magazine are blurry, but by the 1960s, he had grown frustrated with the magazine’s conservative point of view and resigned to pursue a solo career, contributing to Look Magazine instead.

One of his most brilliant works from this period was The Problem We All Live With (1963), depicting Ruby Bridges, the first African American child to attend an all-white elementary school in New Orleans, Louisiana under federal protection.

He would capture another of those real-life frames and convert them into art, with the difference that this time he would step beyond the idyllic images of suburban life and confront the realities of segregation. He would demonstrate and communicate to everyone the issues of racism that the country was living through, proving that his art could be both beautiful and socially urgent.

Norman Rockwell’s art captured the joys, struggles, and hopes of Americans in his time. Today, even as our world and culture look very different, where TikTok trends, Labubu toys, and pop music dominate, his work reminds us that storytelling and hope are timeless and can be achieved. By looking at his illustrations, we don’t just see the America of the past, we discover lessons about courage, justice, and the everyday moments that define us, even if they’re corny or brilliantly crafted. I truly hope that this brief article translated the curiosity I felt about him to you.

Maybe the next time we scroll past a viral trend, we’ll pause to notice the ordinary and extraordinary stories unfolding around us, just as Rockwell did nearly a century ago.