The views expressed in this article don’t necessarily reflect those of the editorial board. This article has been edited for clarity.

There’s a structural and spiritual gap in our institutions.

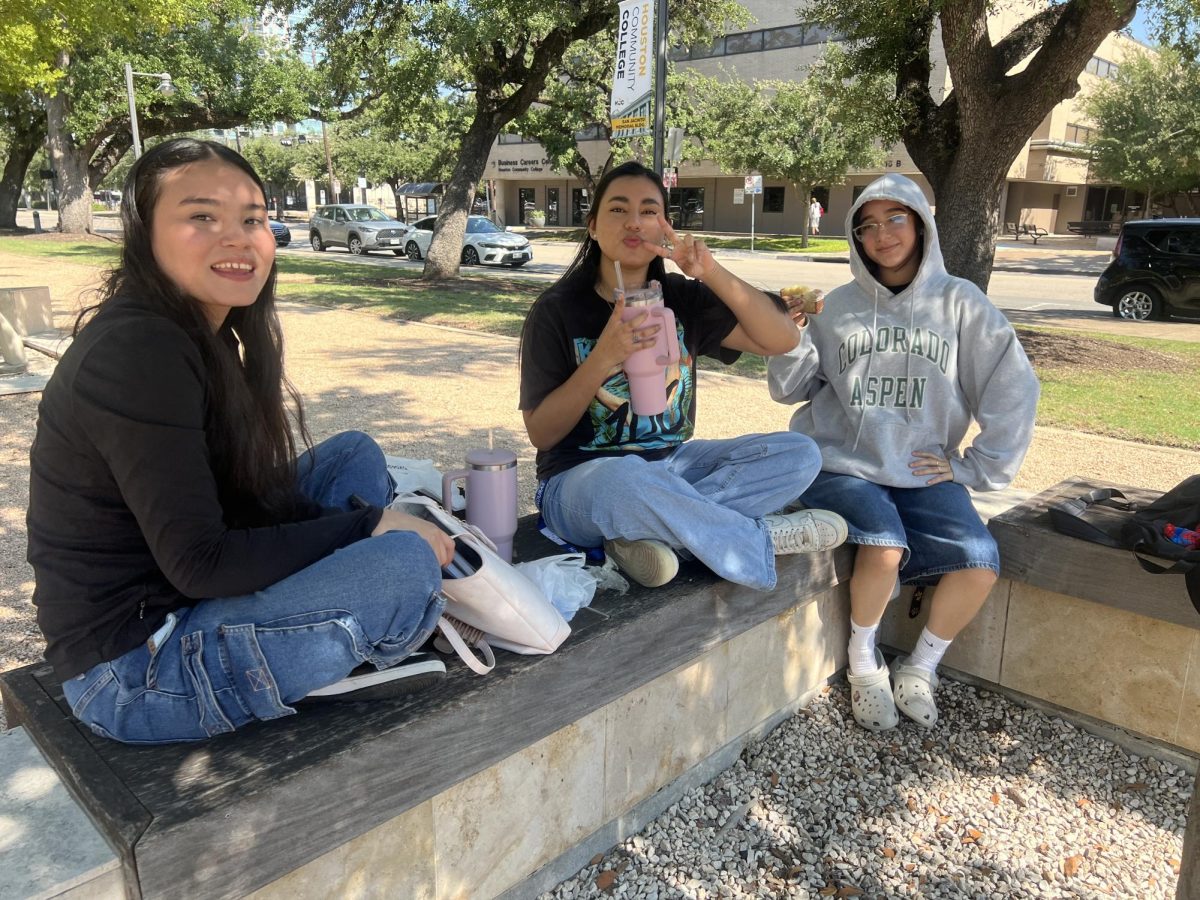

I invite the reader to reflect on people’s opinions about institutions, governments, NGOs, and organizations. What do they all have in common? What is the general feeling toward these groups? Today, we live in a cycle where society deeply mistrusts both public and private institutions.

Strategic communication now finds itself right in the middle of this generational shift. The factors that once made up the ABCs of communication have been overused to the point where audiences receive information faster than ever, whether from the tiny object in their pocket or the TV that dominates their living room.

The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, reports that 61% of people worldwide feel that governments and businesses favor narrow interests and benefit the wealthy, contributing to widespread grievance.

This doesn’t just reflect social fatigue; it shows the urgent need for institutions to transform how they communicate. Words are no longer enough. What we need are concrete, transparent, and consistent actions that support every message. This is the job of strategic communicators, who must go against the wave of general cynicism and reconnect with what people want and need.

A notable case of poor institutional communication is Wells Fargo which faced backlash for opening millions of unauthorized accounts to meet aggressive sales goals.

So how did the company respond?

Their first response was weak and lacked true responsibility. They took too long to offer a real apology or a detailed plan to fix things. Worse, they blamed “a few” low-level employees, which only made people angrier and exposed deeper cultural problems in the company. The result was a damaged reputation, millions in fines, stock losses, and long-term distrust.

Now compare that with a company like Patagonia. When they announced that they were transferring ownership of the company to a climate-focused trust and the Holdfast Collective, they did so with transparency and purpose. They used press releases, storytelling, and interviews. Also, they gained trust, a better reputation, and stronger relationships with their consumers.

Another great example of institutional strategic communication was the government of New Zealand during the early months of COVID-19. Their combination of press conferences and clear guidance built high levels of public trust. In a time of uncertainty, New Zealand showed how consistent communication can strengthen credibility even during a global crisis.

Good institutional communication usually begins with three fundamental pillars:

1. Active listening:

Based on the two-way symmetrical communication model by James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, every strategy begins with understanding the social, political, and cultural environment. That doesn’t just mean looking at data, it means knowing how to read the emotions of the public.

2. Clear and flexible messaging:

Institutional messages can’t be generic. They need to be honest and ready to adapt across platforms and formats.

3. Quick and smart crisis management:

In a technologically advanced system where news spreads in seconds, institutions should move fast and work together. That means having a trained team not just to respond, but to anticipate a crisis before it even hits.

The goal is not just to convince, it’s to rebuild trust.

This objective might seem impossible right now, but there is hope. If communicators lead with ethics, empathy, and truth, their actions will matter more than their statements. And if those actions help and stick with people, then we’re doing what public relations is really about: building long-term, meaningful relationships with our public.

According to Edelman, only 36% of people believe that the future will be better for the next generation. But if we start communicating with purpose, maybe we can turn that number upside down. The future isn’t written yet, but communication might be the way we choose to write it.