‘#Je Suis…’, educate and react with peace

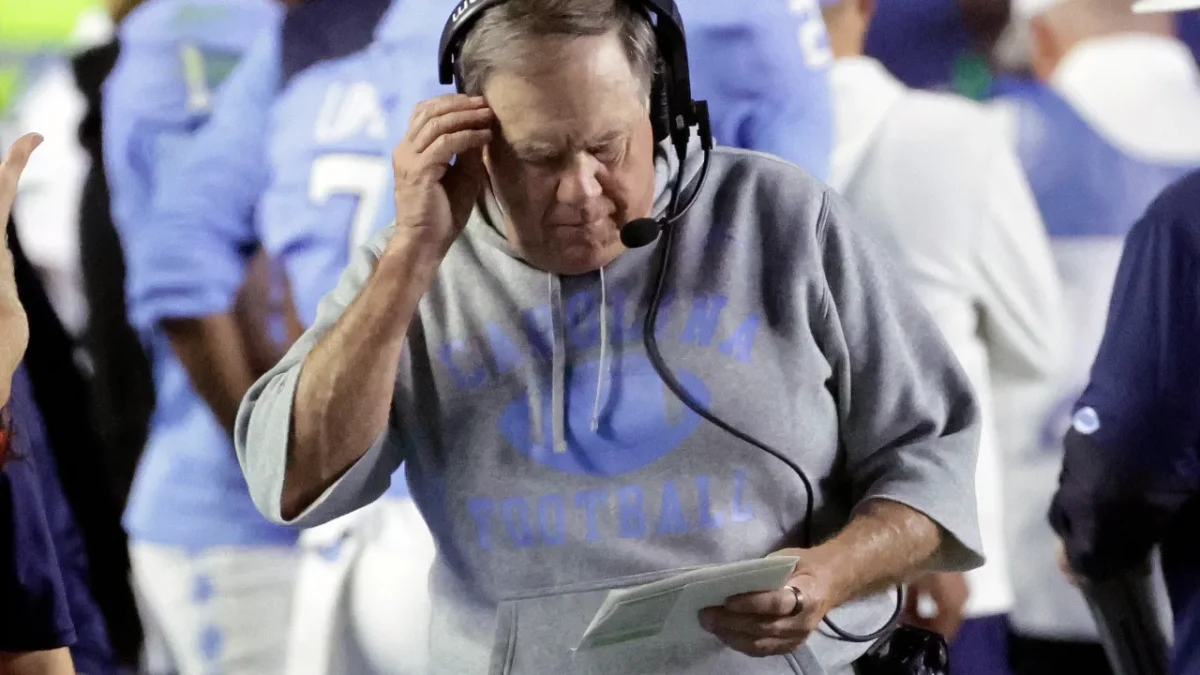

(AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

A woman and a girl light candles at floral tributes at a memorial site at the Place de la Bourse in Brussels, Saturday, March 26, 2016.

April 1, 2016

Over the past four months Europe has seen two terrorist attacks in particular that seem to capture the spotlight of radical violence—one on Nov. 13 in Paris and another recently on March 22 in Brussels.

In response to the horrific attacks in Brussels, there was an explicit call for solidarity.

With the joint death toll standing at about 160 individuals—which the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant or ISIL claims responsibility for—these attacks have been the most violent in France since World War II and the most violent in Europe since the Madrid train bombing which killed approximately 190.

However, our limited scope of attention should also turn to other countries throughout the world, which are experiencing similar and often more fatal events.

Since June 2015, Turkey has experienced seven major bombings, five of which were claimed by ISIL, accounting for 229 deaths in the span of 9 months. Major cities, home to well over millions of Turkish civilians, such as the capital Ankara, Istanbul and Diyarbakır were all targets.

Through that time, where was the worldwide support for Turkey? Where was the guise of hope for Turkey like the sweeping amounts of Facebook profile picture changes and ‘#JeSuisParis’ hashtags from around the world?

Without diminishing the horror of the merciless acts that happened in both Brussels and Paris, we should ask: why similar responses for non-European countries have yet to hit mainstream and widespread conversation?

Understandably, Western European media are generally more concerned with Brussels due to its close proximity.

While that is somewhat justifiable, Eurocentric attitudes and hypocrisy has nothing to do with the lack of attention on Turkish conflict. Questionable is whether or not it is a true lack of attention or a failure to recognize what is happening around the world.

To have more sympathy for something that happens in a neighboring country does not constitute for a lack of care and solidarity for a place with far more internal issues and reciprocal attacks.

Inherently, the “quick fix” for this supposed justified hypocrisy is to recognize that each country has their own respective problems, which they must deal with.

With a common enemy and similar outcomes the questions, ‘What about Ankara?’ or ‘What about Turkey?’ should be followed by ‘Why?’

To ask ‘What about Ankara?’ or ‘What about Turkey?’ ensues that the attention these places deserve is not given—which is true—but ‘Why?’ gives more insight to the purpose and history of these fleeting, yet persistent events.

The creation of ISIS took place overtime, after a branch of al-Qaeda filled the power vacuum void left by the U.S. invasion of Iraq, with the regime of Saddam Hussein taken out of power. Acting as a threat to Western interests and worldwide safety the jihadist groups threaten numerous parts of Africa, Europe and the majority of Middle Eastern nations.

In regards to Africa, the Boko Haram regime holds similar ideological values as ISIS—which adheres to the principles of religious persecution and violence—along with boasting arguably the deadliest terrorist regime in the world.

They are responsible for the kidnapping of over 200 young schoolgirls in Nigeria along with countless bombings and attacks within Nigeria, Cameroon and Chad.

According to the Global Terrorism Index, Nigeria has seen a 300 percent increase in terrorist related attacks from 2013 through 2014, with an increase in 5,662 deaths. In 2014, Boko Haram was responsible for 6,118 deaths.

But again, ‘why?’ is the question for the seemingly never-ending destruction and violence, this time in Africa.

An informative answer looks to history, through much of the nineteenth century, a period labeled the Scramble for Africa; saw the colonization of a stout majority of African nations by European powers, including France, Britain, Germany and Belgium.

Countries such as the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast—currently Ghana, Nigeria, Morocco, and many more, were under the control of European nations who sought to extract raw materials and set up religious and economic principles throughout.

For example, British controlled Nigeria was injected with Christian influence that figuratively split the country between northern Islamic Nigerians and Southern Christians. Mohammed Yusuf—the founder of Boko Haram—was a radical Nigerian Muslim focused on expunging Western practices and teachings from Africa.

Territorially dividing the continent up, one of the main supporters of the colonization of Africa was the King of Belgium, Leopold II, who took control of what is currently the second most populous country in Africa—the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Leopold used his commercial ties to orchestrate the killing and maiming of individuals in the Congo Free State for increased production and wealth. This in turn created the institutionalized racism between colonial associates and natives.

After the Belgian government took control of the Congo Free State, economically they did considerably well, but the social issues involving racism continued to grow until Congo received its independence.

Congo exercised stark resistance of the Belgian-Congo’s imbalance of racial autonomy. Revolts, looting and destruction of European property started combatting the lack of equality.

Local leaders, Patrice Lumumba and Joseph Kasavubu, were large players in the beginning of political structure in the newly independent nation.

Left without a structured political system, from 1908 to the present, Congo has seen the effects of colonialism on a country—including a brief dictatorship under Mobutu Sese Soku, dynamic leadership changes and shifts in power, a crippled economic system and inherent violence.

Paradoxically, the plight of Congo can be traced directly back to Belgium, recently at the end of its own devastating terrorist attack.

The increasing threat to freedom across the world cannot be met with ignorance of issues similar to Ankara and Nigeria and a lack of solidarity for every nation experiencing these issues—instead it should be combated with a knowledge and awareness of the causes of current worldwide complications.

What seems like the aggression and unrivaled destruction stemming from a particular ethnic group for no just cause, is possibly a response of years of civil unrest due to ethnic or religious persecution met with the violence needed for attention.

Commenting on the recent attack in Brussels President Obama stated, “We must unite, we must stand together,” to resist “the scourge of terrorism.”

In the face of disaster one can look to a comfortable lie or the harsh truth to answer the question of ‘why?’