The big oil problem

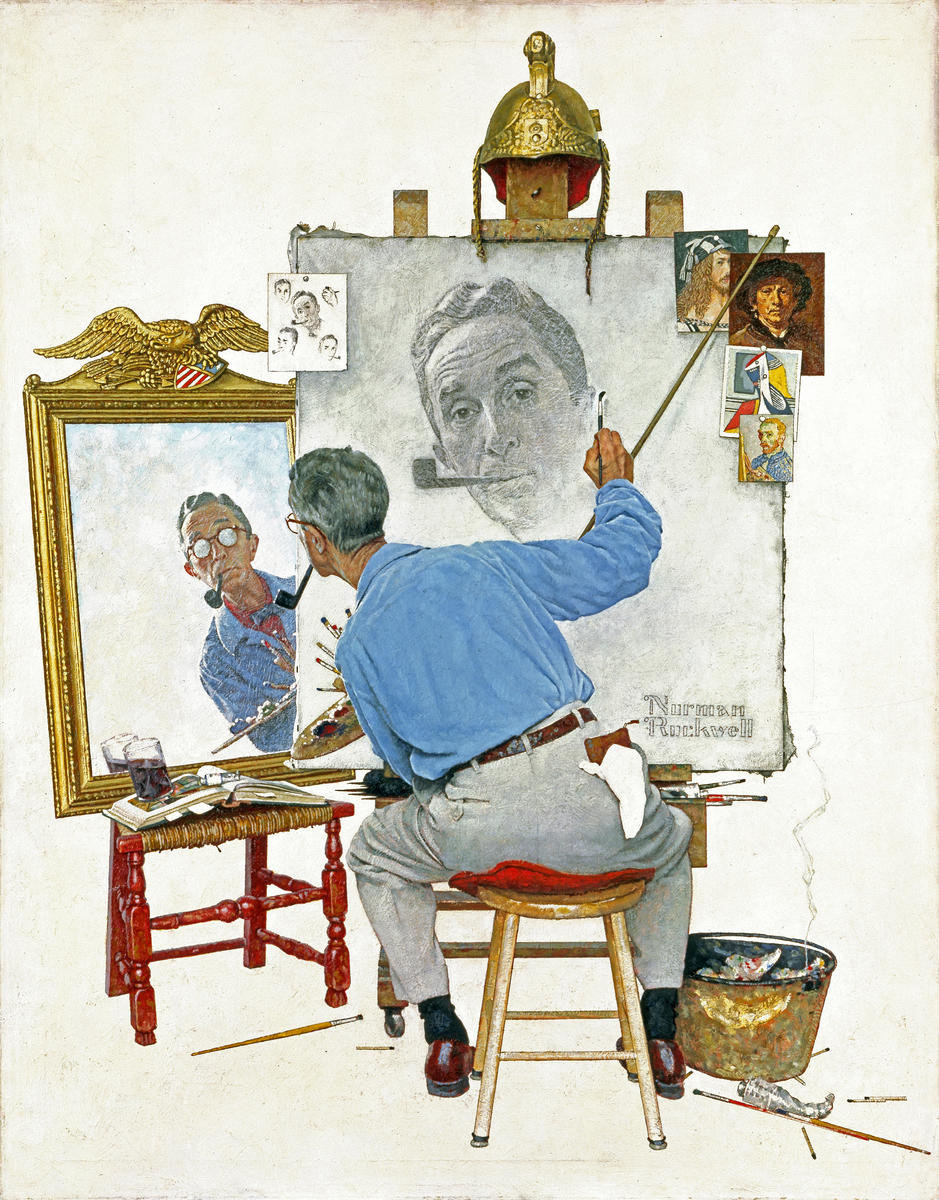

An oil pump works at sunset Wednesday, Sept. 30, 2015, in the desert oil fields of Sakhir, Bahrain. Consumer prices across the 19-country eurozone fell in September for the first time in half a year as energy prices tanked, official figures showed Wednesday, in a development that’s likely to ratchet up pressure on the European Central Bank to give the region more stimulus. The 0.1 percent annual decline reported by Eurostat, the EU’s statistics office, was widely anticipated following the recent drop in global oil prices. (AP Photo/Hasan Jamali)

October 9, 2015

The oil industry has long been characterized by a never-ending boom and bust cycle. Most memorably for Houstonians, the oil slump of the 1980s and the end of the embargo saw one in seven of us lose our jobs and simply go elsewhere for work – turning the city into a sort of bust-town.

The present situation hasn’t yet become quite so bad, but as the price of a barrel of crude bounces between $30 and $40, the effects are certainly being felt among the energy employees of Houston’s glittering Downtown skyscrapers.

So why is all of this happening so quickly? In short, there is too much supply and not enough demand.

The energy sector, and indeed the entire economy, swelled in post-recession China. The government began importing large amounts of crude; driving worldwide averages to more than $100 a barrel.

Concurrently, newly developed techniques like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing — or fracking — allowed American oil companies to extract crude from shale, slowly saturating the market.

As China’s economy began to shrink, they slowed petroleum imports and began to look within the state for energy solutions — reducing income for oil companies abroad. Back home, the supply of oil from new sources increased from domestic production and economic growth slowed worldwide, causing the price to plummet.

In an effort to maintain market share, the OPEC countries continued to pump more oil into the global market. With their low costs of production, member nations are more prepared to weather the economic consequences of a failing market.

That hasn’t been the case Stateside – or anywhere else. Crude oil prices have fallen 50% from mid-2014 to less than $40; and more than 170 thousand energy workers are being laid off worldwide.

The effects of the drop are being felt at every one of the companies that make up “Big Oil” – the number of oil and gas job openings worldwide dropped in half from 24,000 to 11,600.

Royal Dutch Shell is cutting more than 6,500 jobs worldwide and Chevron has announced plans to lay off 1,500 jobs worldwide beginning in October — 950 of the jobs getting cut are in Houston.

In their letter to the Texas Workforce Commission, spokesman Ed Spaulding said, “Chevron is taking action focused on increasing efficiency, reducing costs, and focusing on work that directly supports business priorities,” reflecting the 90 percent drop in their second quarter profits.

Chevron employees will be given two months notice beginning Oct 12.

Who will be laid off is to be determined through a sort of “weed out” process — employees have had to reapply for their own jobs — and hopefully can prove their continued worth to the company.

Still reeling from the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP has taken one of the hardest hits in this slump. From their headquarters in the Energy Corridor, BP has announced more than $1.5 billion will be spent restructuring and laying off its upstream staff.

Exxon has not announced any layoffs — and, in fact, has actually slightly raised payments to investors — but posted the lowest quarterly result this year along with Chevron.

Smaller service companies are being hit even harder — National Oilwell Varco said its well bore technology unit is closing an office in Willis, TX, laying off 150 employees starting in mid-August.

Weatherford Intl. says that among a falling stock price it is, “taking advantage of the downturn to develop a leaner structure and a tighter organization.” Originally planning to let 10 thousand employees go, the company completed that goal and raised the target number to 11 thousand.

Additionally, they have closed more than 60 operating facilities across North America and will close 30 more by year-end 2015.

However, as the saying in the industry goes, “the closer you are to the drill-bit, the more your job is at risk.” As bad as the situation looks in the office, the bulk of layoffs have been made in the oilfield.

The average pay for a roughneck is about $20 an hour, but overtime and hazard pay mean oilfield workers often take home almost $100 thousand a year.

As service companies close facilities among reduced demand, those at the root are often the first to go. According to data gathered by Baker Hughes, the number of oil and gas rigs in the US has dropped 46% to 988.

Since fracking became popular, more and more workers are coming from non-oil backgrounds, and when their rigs close and their jobs disappear they have to take a major pay cut in their next jobs.

The effects of the oil downturn aren’t just being felt in the US. BP CEO Bob Dudley says most of the cuts will be made in Aberdeen, with job losses here in Houston as well.

Stavanger, sister city to Houston, and once the booming oil and gas hub of Northern Europe, has one in three jobs tied to the energy sector. Caused by the loss of thousands of jobs, the housing market is crashing as people leave – as they did here so many years ago.

SAS, who just introduced a non-stop flight from Houston to Stavanger last summer, has cancelled its six flights a week to the fourth largest Norwegian city.

Though consumers are happy paying $2.29 a gallon at the pump, the big question everyone wants answered is: “When oil prices will rebound?” – It’s not a problem easy to solve.

Shell CEO Ben van Beurden told BBC Radio 4 that he doesn’t know if oil prices will recover and Goldman Sachs research chief Jeffrey Currie, released a warning that oil prices could sink as low as $20 per barrel.

The recent nuclear deal with Iran will eventually add as much as a million barrels a day to the already saturated global market of 94 million barrels, further crushing hope that prices will rebound anytime soon.

Though analysts say prices will eventually come back, there is much disagreement on when, or how fast. Ironically, so many jobs being lost could be a deciding factor – with less people on the rig getting oil out, the supply could lessen over time and drive the price back up.

That’s just one of the theories put forth – unrest in the Middle East driving up prices; China relaxing its lending practices; and the lower price of oil raising demand could all also help us solve the big problem.

But even with all of this data and analyses and projections, nobody knows what the price of oil will be next year, next month or even next week. The people who have lost their jobs in the downturn are the visible casualties of a volatile industry the whole world depends on.