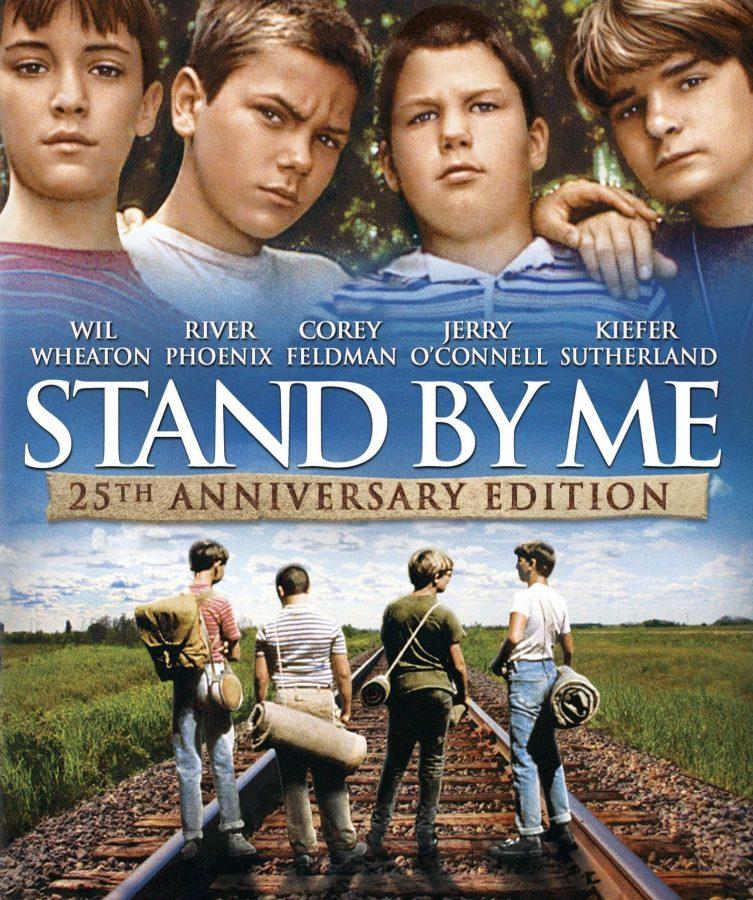

In Retrospect: Stand By Me

February 11, 2017

There’s a clever subtlety to Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me. It’s there just off in the background. Casual viewers won’t notice it so much, but those paying attention just might.

The film tells the story of four boys growing up in the small town of Castle Rock, and of their journey into the surrounding forest in search of a dead body. It is the ability of both Reiner and novelist Stephen King to get away with such a premise that is the first clue to the film’s ingenuity. Based off a novella collected in King’s 1982 anthology Different Seasons, the basic concept of the movie is one that should equal automatic box-office poison. In an era in which E.T. was still the most popular flick of the decade, it almost seems impossible that SBM even made it past development.

It has the look and feel of a Spielberg movie, yet instead of an adventure we are treated to a soul-searching meditation on mortality and meaning. The story’s heroes, Gordie, Chris, Teddy, and Vern all look like Goonies extras until you spend just five minutes listening to their tree-house banter. Parental conflict is a common theme in Spielberg, yet even he never went so far as to have one of his screen dads threaten to shut their kids up in a closet, or do what Teddy’s dad tried once when his son was a kid. The closest we get to a normal Spielberg protagonist is the main character, Gordie. He’s a thoughtful kid, and a budding writer with potential, yet he’s forced to live in the shadow of his long dead brother. This older brother was always placed in the spotlight by parents who, perhaps, never really planned on having another. Either way, the fact is that Gordie is forced to live under a roof that’s unaccustomed to change. By agreeing to accompany his friends into the woods, Gordie will find himself forced to come to terms with these changes, and the uncomfortable truths about himself, his family, and even the life of his Norman Rockwell like town.

What the audience is treated to is a slow overturning of the tropes of the typical 80s kid’s movie. The journey the characters take does contain a sense of wonder, but it’s a shadier version that owes much the Gothic genre which King has made his home. In his intro to a published screenplay, King said that:

“I write about small towns because I’m a small town boy…and most of my small town tales…owe a debt to Mark Twain…and Nathanial Hawthorne…(ix)”.

By citing Hawthorne’s short story Young Goodman Brown in the same intro, King provides the proper lens through which to view his work as a whole, and Stand By Me in particular. In his book, Hollywood’s Stephen King, scholar Tony Magistrale holds that “In Stephen King’s best work, a bridge exists between the immediate and familiar landscape of contemporary America and the predominant concerns found in the tradition of nineteenth – century American literature. King’s…close scrutiny of character, tradition, and the clash between civilized values and the wilderness of nature find some of their closest points of comparison in the narratives of Nathaniel Hawthorne (209)”. What we have then is a hybrid film combining the themes of the average 80s kid’s flick mixed into the darker themes of a New England Gothic tradition.

While Stand by Me contains no fantastic elements, it’s episodic nature give the structure of a boy’s adventure yarn. If it is an adventure, however, then there is an element of subversion in the way King and Reiner handle the material. The characters go on a journey; however, their quest has a morbid goal. They encounter challenges that often reveal unpleasant facts about themselves. While its usual for character’s to have their lives threatened at some point in this type of tale, here the stakes are higher as when Gordie and Vern are almost plowed by an oncoming train. If all these ingredients seem so familiar yet foreign, then perhaps SBM can also serve as a filmic equivalent of a gateway drug. What Reiner and King have done is give their audience a perfect example of a Gothic quest story.

If there is anything that separates the Gothic from other genres, it is the focus on the darker, more macabre aspects of the narrative. Gothic stories often have a more personal element because the setting encountered by characters in such plots is often an extension of the faults the protagonist must overcome if he wants to achieve his goals. In Gothic terms, this usually means clearing out all the skeletons in the closet.

At its heart, though, all these ingredients find their center in a coming of story. Despite his talents, Gordie doesn’t really have any goal at the film’s start because of the way his parents have dismissed him. As his makes his way the backwoods of Castle Rock, he grows more aware of aware of his own flaws, and in particular those of his friends. At first, Gordie is reluctant to acknowledge his own problems, needing Chris to point them out.

By the time, he reaches a showdown with the film’s villain, played by Kiefer Sutherland, Gordie is able to recognize all the social hypocrisies of his town that have conspired in various ways to keep people like him or his friends down. This hypocrisy is on display in an anecdote Chris relates about his school teacher pilfering student lunch money and then blaming it on him. Ultimately, the corruption of the town is summed up in Sutherland’s character. By taking a stand for both himself and his friends, Gordie is able to make a change for the better. At the end, he’s realized who he is and what he has to do to succeed.

The moral of King’s story seems to revolve how people isolate themselves, and how it is sometimes necessary to reject those societal forces that hold normal life in check. It’s quite a lot to pack into just an 88 minute film. However, the best stories are often capable of packing a lot of complex ideas into a simple looking package. When all is said, it’s a pretty clever film.